For day 3 of the Microbial Advent Calendar, let’s have a look at the Beewolf (Philanthus triangulum). Neither a bee nor a wolf, it is, in fact, a predatory wasp that actually hunts bees. Although the adult does not feed on bees, but on plant nectar, the females hunt bees to feed their offspring. When they sting the bees, they are not killing them straight away but paralyzing them to be consumed by the future larvae in due time. The females dig burrows in sandy soils and create a “brood cell” which is where she will store up to five paralyzed bees for a very hungry carnivorous larvae. Once fed the larvae will secrete a cocoon and stay in a hibernation state to pass the winter and will emerge when the temperatures raise again.

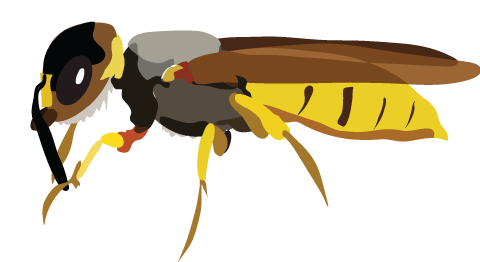

Because I really like how my wasp turned out in the end, here is the full version of the drawing!

The problem with protecting your future generation in a moist underground chamber surrounded by dead bees is that you expose the egg, larvae, and cocoon to a multitude of opportunistic pathogens, such as bacteria and fungi. But the beewolf has a trick up its sleeve, well in its antenna to be more accurate. Female beewolves have a special gland in their antenna where they house Streptomyces, which as its name doesn’t suggest is a bacteria. When preparing the brood cell, just before laying the egg on one of the dead bees, the beewolf will squeeze the gland and spread the bacteria in the chamber.

The bacteria will grow in the chamber and will secrete a large arsenal of antimicrobial compounds that will keep any other pathogens at bay long enough for an adult to hatch from the cocoon. On its way out the new female will pick up the good Streptomyces and repeat the cycle.

If you want to learn more about this cool symbiosis, check out this paper from Sabrina Koehler. It is a good overview of the system. You will also want to check out Martin Kaltenpoth’s lab, they are currently working on this topic!